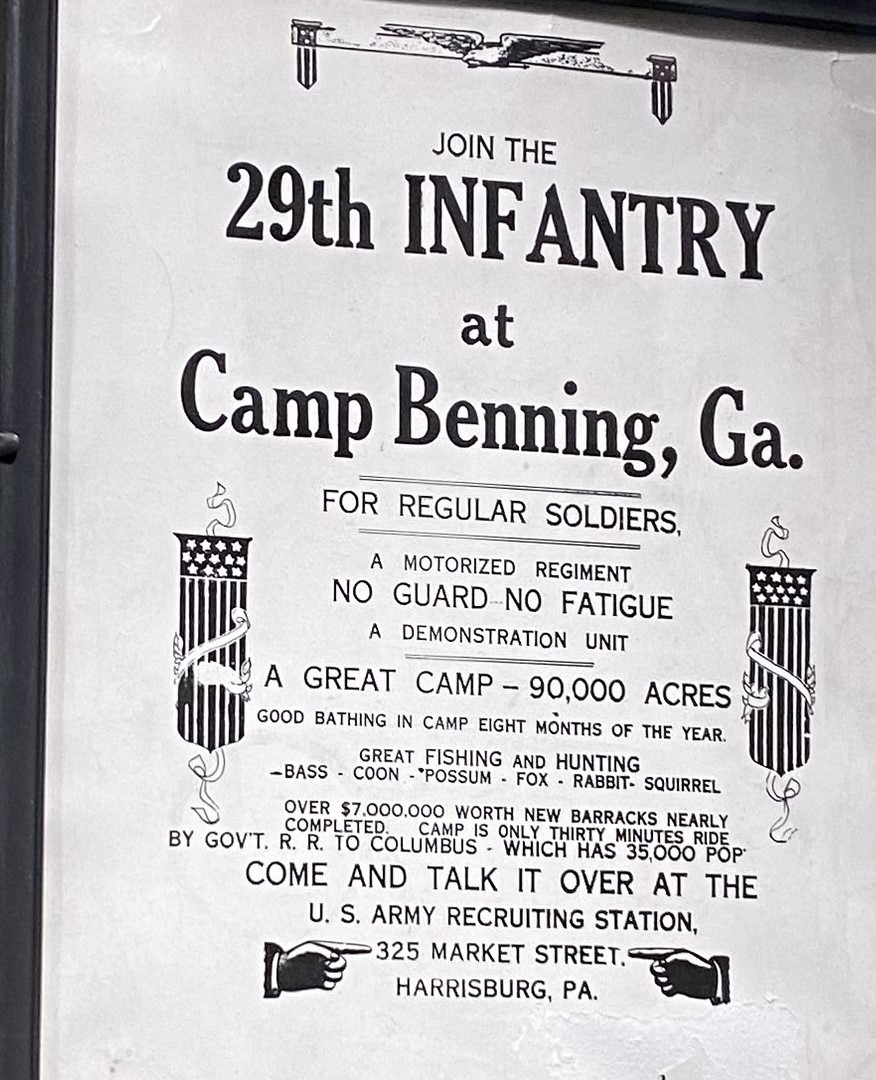

A couple of months ago, I attended a prescribed fire conference at the National Infantry Museum in Fort Moore, just outside of Columbus, Georgia. After finishing the official part of the meeting, we were allowed to wander through some of the exhibits. Among the relics was a recruiting poster from the 1920s – back when the post was known as Camp Benning. The spiel suggests an easy life, good weather, new barracks (“nearly completed”) and “Great fishing and hunting”. But what caught my eye was the list of game species: raccoon, opossum, fox, rabbit, and squirrel. One conspicuous omission: white-tailed deer. Why wouldn’t they advertise a game animal that is so plentiful today?

Deer were plentiful all across the Southeast when the first Europeans arrived. As the colonies established and spread, hunting for food and for trade items (deerskin was a premium leather for exportation to Europe) decimated the population. In the 19th century, the growing cities demanded meat of all kinds, and market hunters were happy to add venison to the menu. The loss of forests to logging and agricultural expansion made the problem that much worse. Laws to protect deer, such as a hunting season enacted in 1840, were largely ineffectual. By the first decade of the 20th century, fewer than a third of the counties in Georgia claimed to have any deer left. I presume Muscogee and Chattahoochee counties, where Camp Benning stood, were not among the fortunate third.

The return of whitetails to Georgia comes down to three things. First, the reforesting of Georgia: in many places, old fields were abandoned, and old cutovers regrew. Governments acquired land for wildlife protection, especially after the Pittman-Robertson Act in 1937.

The second factor was the restocking effort. A U.S. Forest Service ranger named Arthur Woody began the process by himself with half a dozen deer released in the mountains in the late 1920s. Federal funds in the ‘30s allowed for a more systematic approach. For some six decades, deer were brought in from a number of other states (including Texas, Wisconsin, Kentucky, and Maryland), and coastal islands of Georgia to be released around the state.

The third factor in the recovery was protection. More regulation, coupled with more rigorous enforcement and public education, allowed the deer herd to expand. Once the state reopened a hunting season, scientific monitoring allowed biologists to assess and adjust management of the deer population.

When I was a child in the early 1970s, seeing a deer was a pretty big deal. Coming home this evening, I saw half a dozen does feeding on the shoulder of the road. This season I’ve put four deer in the freezer. We now have a million, give or take, white-tailed deer in Georgia, and the most liberal harvest opportunities of my life.

I heard tell they can even hunt deer on Fort Moore.

Additional Resources:

enough for a doe to recognize her offspring, but not enough for her (or a coyote) to easily trail it. Their second asset is their reddish-brown color. That seems counterproductive until you realize that most predators don’t see well in the red range of the spectrum; like many color-blind humans, coyotes and bobcats cannot easily distinguish between red and green, so a reddish fawn in green grass is pretty unobtrusive. Furthermore, they are dappled with white spots. Perhaps it breaks up their visual pattern further, or perhaps it mimics the dapples of sunlight filtering through the leaves.

enough for a doe to recognize her offspring, but not enough for her (or a coyote) to easily trail it. Their second asset is their reddish-brown color. That seems counterproductive until you realize that most predators don’t see well in the red range of the spectrum; like many color-blind humans, coyotes and bobcats cannot easily distinguish between red and green, so a reddish fawn in green grass is pretty unobtrusive. Furthermore, they are dappled with white spots. Perhaps it breaks up their visual pattern further, or perhaps it mimics the dapples of sunlight filtering through the leaves.

You must be logged in to post a comment.