When I was a little lad (back when they included cuneiform on multi-lingual instruction sheets), I got a sled for Christmas. Several years went by before I had actual snow to test it on, although I do remember sliding down a hill of ice. Where I live, ice is a common hazard of winter: rain followed by a cold night, or worse – rain that freezes on contact. Freezing rain is to be feared. Not only does it slicken stairs and pavement, but it weighs down tree limbs to the point of breaking. A forecast of freezing rain sends us filling the bathtub and checking flashlights in preparation against downed power lines. We seldom get winter wonderlands in our part of the Piedmont, only hazards and inconveniences.

This month, the heating of the upper atmosphere, perhaps ironically, disrupted the normal pattern of the polar vortex, sending frigid air blasting southward. Weather prognosticators warned the nation to brace for a bitter storm. Our run up to last weekend was a flurry of storm prep, with the expectation that power could be out for days. Snowpocalyse, for us at least, was thankfully over-advertised. We woke to a layer of sleet and ice, but also running water and lights. Treading carefully and driving as little as possible was the order of the week. Life went on.

“But wait, there’s more,” cried the meteorologists, declaring another wave of cold and wet was on its way. On Friday evening, we checked that last weekend’s preparations were still in place, and braced for ice and snow.

By mid-morning on Saturday, a few tiny flakes began floating down, heralding a heavier snowfall that was sticking before noon. Snow petered out around 3:30. Depending on where you looked, it lay at 2-4” deep, and powdery with that soft crunchy-squeak sound. I took some of our dogs out for a spin. They stuck their muzzles in the snow like they were searching for where the smells went.

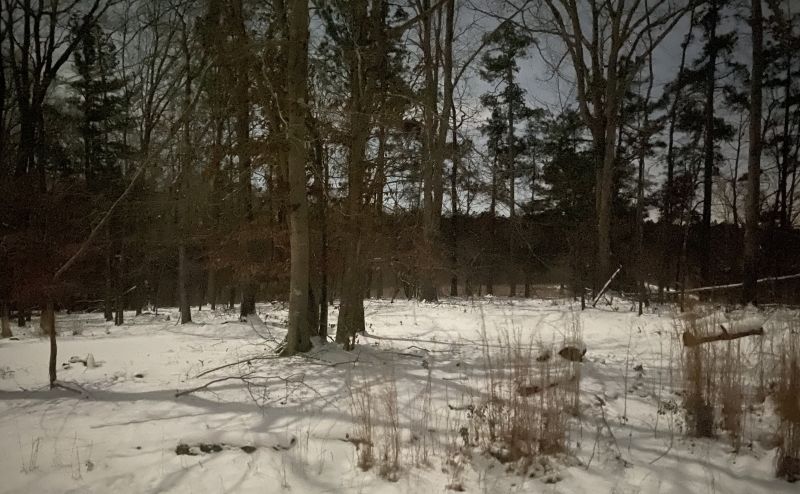

After dark, we were treated to a brilliant full moon and a cloudless sky, which made for sharp shadows on a silver-gray ground (below). Between a decline in drivers willing to brave the roads and the muffling effect of the snow, the woods were truly quiet in a way they rarely are in the crowded spaces between cities.

Sunday dawned clear and well below freezing – rising just above freezing by afternoon. Already, the roads and driveways were clearing. The view in field and forest was still brilliant white, but patches of tan grasses and brown leaves dotted the vista.

Monday’s temperature shot up to the lower 50s. The sun ate away at the snow. By evening, the weekend’s fine powder blanket was reduced to a few coarse icy clumps huddled against the north side of trees. By mid-week, the show was over.

As a kid, I envied my northern counterparts their months of deep snow. As an adult, I can enjoy the novelty of an appreciable snowfall and still be glad to return to dry ground within the week. Probably just as well I don’t still have a sled.

You must be logged in to post a comment.